Have you ever bought a couch? I have. I spent so many Saturdays listening to poorly paid salespeople stroke fabric swatches the way most people do a cat and sink their behinds deep into cushions to demonstrate pneumatic lift. Or otherwise.

That’s time I’ll never get back.

I did ultimately find my couch. ‘My’ couch because it is very ‘me’. At least the ‘me’ I was and wanted to be and now definitely am. Partly because now I spend ample life-time, stretched out, reading and wrestling my kids on it. It is an object that plays a central role in shaping my existence within a room and a house thoughtfully constructed and arranged. Also because, when guests call, they remark on how nice and ‘me’ it is!

There is no such thing as empty space. Empty space is space with nothing to clutter it and therefore represents freedom and a lightness of being. It is full of meaning and emotion.

Good architects produce buildings that impress and surprise. But great architects understand space – the relationship between body, mind, built form and space. Great architects design spaces that reflect and embody the identity of the people who live within them.

Why then do we not see more great architecture in health and aged care? Granted, there are some notable exceptions but on average things are average – and that means an average or worse experience for people ageing in place or receiving treatment. And that means barriers to wellbeing and recovery.

We need more human identity in aged care architecture.

“One of the great, but often unmentioned, causes of both happiness and misery is the quality of our environment: the kind of walls, chairs, buildings and streets we’re surrounded by.”

– Alain de Botton, The Architecture of Happiness

Having worked for many heath and aged care providers, large and small, and having looked in detail at the processes of architects designing aged care facilities, I believe there are two key reasons for this.

- Aged care providers do not invest in deep, ongoing relationships with the communities they serve in order to align community needs and expectations with building enhancements and service innovation.

- Architects do not consider deeply enough the desire of older people and families for their lives not to change when they need aged care.

How to solve these two problems?

The design of care plans and lifestyle programs considers the individual and the group; these are loudly broadcast tenets of the industry. But how much do they address identity: the characteristics, values, attitudes, and beliefs that make us who we are?

Unless I have a multiple personality disorder or an identity crisis, I am fairly comfortable in my skin. The older I get, the less likely I am to question my values, beliefs and attitudes. I know what I want and I want what I like.

The personal identity of consumers informs their buying decisions because our purchases say a lot about who we are. We are keen to align our purchases with our values and leave a good impression on our own sub-cultural communities – defined by interest and, often, geography. After all, our choice of place to live is informed by our identity and vice versa.

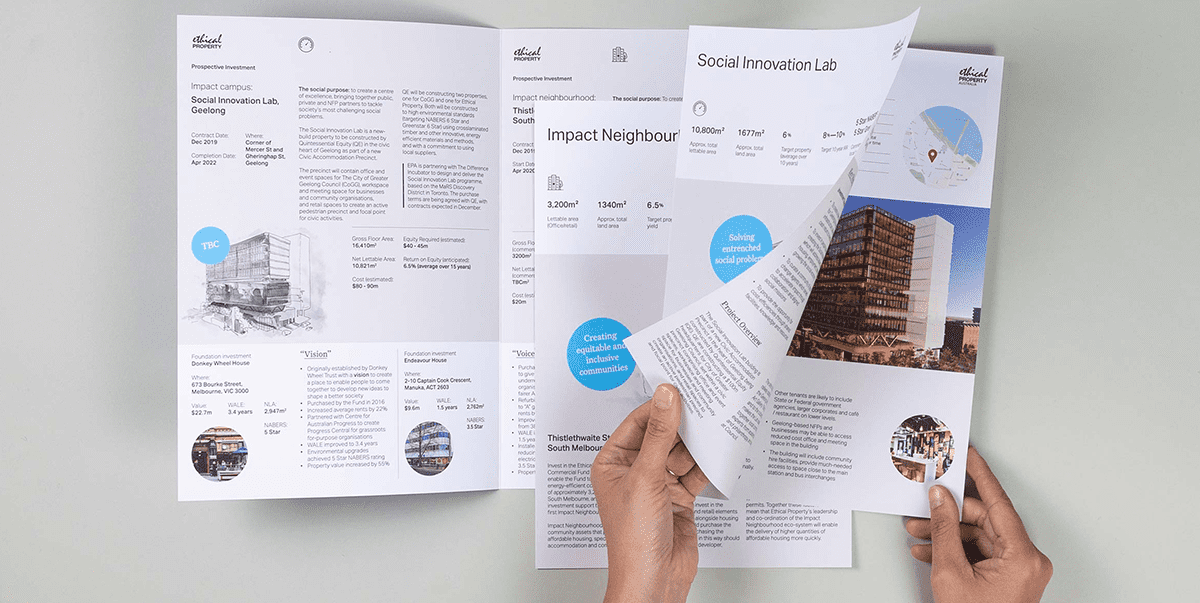

Understanding community identity – via research as engagement – means understanding place. And creating a sense of place that enables older people to continue living a fulfilling life as they have at home should be the primary goal of aged care architecture. It should define the outward aspect of the facility, light, line, and inter-connectivity of rooms and passageways. The entrance should introduce the organisations philosophy. A balance should be found with permanent comfort and ephemeral surprise via changing colour, art and gardens.

These are just some of the aspects of building design that we cherish at home and in our neighbourhoods. We never stop evolving our houses from the tiniest details (a brass hook, a door stop) to grander designs (a second level with infinity pool!).

Place branding teaches us that communities want landmark assess and community activities to call their own. Aged care facilities can be the landmarks people remember and promote when that are telling the story of their strong, caring, innovative community. Be bold – but be bold with local people.

Providers need to start matching their architects with consumer insights and brand identity specialists to create spaces that are admired – and referred.

As the sector changes, becoming more competitive and specialised, these facts will remain true for every company serious about achieving the highest levels of health and wellbeing for people, and a sustainable, growing operation.