We’ve just had another round of apologies from ‘boys being boys’, Eddie McGuire and co. This time, it was about his vicious pledge to have prominent sports journalist, Caroline Wilson, drowned.

It’s a culture that is pervasive. Where boys egg each other on, say things, and on occasion do things that denigrate and humiliate. It’s pack mentality paraded as virtuous under the guise of humour. Whether directed towards a man or a woman, it’s pretty disgusting.

If our culture allows revered men to revel gleefully in their misogynistic or violent inclinations; if these men hold a platform where they model what it means to be a “good Aussie bloke”; if we laugh when they decree that thuggery is needed to cut down those who accrue power and respect, especially if she dare step on their turf; then that says something about our culture.

Do I think it’s OK for Eddie and his ilk to make the occasional joke at a woman’s expense? Of course.

Do I think that a man who has never done this before, will – as a result of a singular broadcast – start abusing his wife? No.

But I do think that boys and men learn from displays like this. And the lesson is that you can happily want to drown a woman who stands up to you. That is not a cultural norm I would want any man that I love — father, brother, son — to have to resist.

And that’s why it’s not OK for us laugh and dismiss this particularly nasty threat as an inconsequential bit of ‘banter’. At the very least, we are entitled to object. And loudly, if necessary.

Because staying silent makes us complicit in a culture where the occasional metaphorical or physical slap-down of a woman who doesn’t ‘know her place’ is OK. And, let’s face it, even with subjectivity aside, that is essentially what this was. After all, ‘she had it coming’ (as would say many of those calling into radio, or commenting online). But despite anything Caroline Wilson may or may not have done to ‘set Eddie off’, I would argue that suggesting she be drowned is probably still not OK. It’s not excusable. It’s just not.

Does anyone see the pattern here, yet?

This is the same narrative that sees one in four Australian women experience physical or sexual violence at the hands of men who claim to love them. One woman each week dieing at the hands of a current or former partner.

For violence to be happening this often, to this many women, something systemic must be going on.

This is more than a few guys, who drink too much, or have bad attitudes towards girls, or just a propensity for violence. This is not just about them. It’s about us.

It’s us permitting a culture to exist where the prerequisites for family violence are fostered. A narrative that excuses behaviours it shouldn’t from men. And that tells women too often that they are to blame, or just to grin and bear it.

It stands to reason and research that if we say and do nothing, this culture, this narrative and this way of being will continue to persist. It’s underlying assumptions influencing us, even when we don’t mean them to be.

But finally, thankfully, and happily, things are changing.

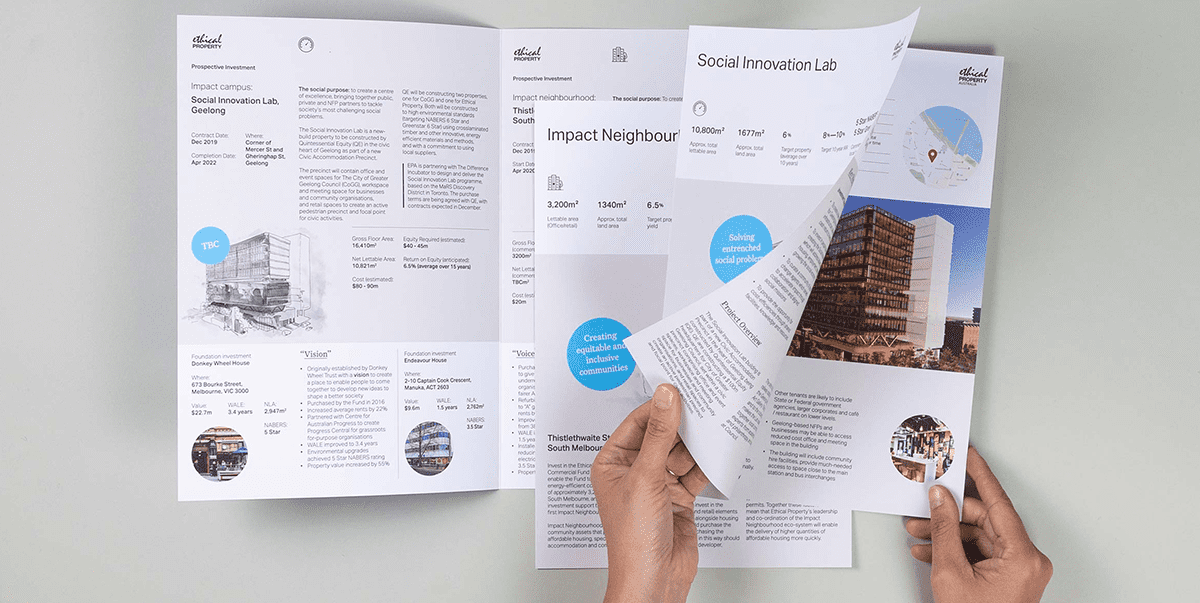

In Victoria this year, we had our first Royal Commission into Family Violence, producing 227 recommendations. In summary, its findings focus primarily on two things:

- On how to make it easier for women in violent home situations to get out; and,

- On tackling perpetrators, including a relatively small number of repeat offenders who account for a disproportionate amount of family violence.

The focus of this Royal Commission is on fixing a broken system, so that it supports rather than thwarts women in vulnerable situations. This is necessary and important work, and needs to happen fast. But it’s a treatment, and not a cure.

To prevent these situations before they start, culture change is what’s needed. And in a world-first approach to family violence, this is the ambition of Our Watch, a national organisation dedicated to the prevention of violence against women and their children.

Underpinned by the real and theoretical power inequality that continues to exist between the genders, Our Watch has developed an evidence-based national framework for the primary prevention of violence against women and their children in Australia.

It’s the first time anywhere in the world that cultural change has been placed at the heart of a strategy to prevent and end family violence.

Here is a snapshot:

It’s an approach that not everyone agrees with.

But if it’s clear that family violence is unique in disproportionate perpetration by men against women, then it stands to reason that something unique about that dynamic —and the context which allows that dynamic to exist — must be at play. There is a body of international evidence that agrees. And it’s on this basis that Our Watch’s ‘Change the story: national framework’ seeks to do just that. How? They have a range of programs to influence the influencers — such as media — and nip attitude formation in the bud among teens. You can read more about their holistic approach on their website.

Vital among this work is demonstrating how this narrative is born and how it pervades. A new government communications campaign seeks to unveil just how our off-handed remarks form part of unconscious attitudes that ultimately normalise the poor treatment of girls and women.

Like drink driving, seat-belts and water saving campaigns that have, over the long-term, been able to radically change how we think about these things, and how we act in relation to them, the combination of cross-sector collaborations, media re-education and government campaigns across Australia is starting to affect cultural change.

And that’s why, Eddie, when you want to viciously attack someone, especially a woman, for doing her job – it’s no longer a joke.